The reasons for companies choosing to create PDFs are perfectly understandable. PDFs protect the document content: unlike Word documents, PDFs cannot be altered or tampered with, and can usually be viewed on any device, irrespective of operating system or installed software. Converting a document into a PDF file is simple and quick to do, whether the original is a Word, Excel or PowerPoint document. The resulting PDF can then be locked, so that the writer or person managing or processing the data has control over who can access or edit it. Furthermore, if a document contains stamps, seals or signatures, as often happens in a legal contract or attestation, for example, these must be handwritten or imprinted onto paper, which will then need to be scanned to a PDF if it is to be shared. PDF stands for “Portable Format Document” and was invented by Adobe. To many, it is a clever and useful device to ensure security, safe sharing of information and effective communication. To a translator though, it can be a headache.

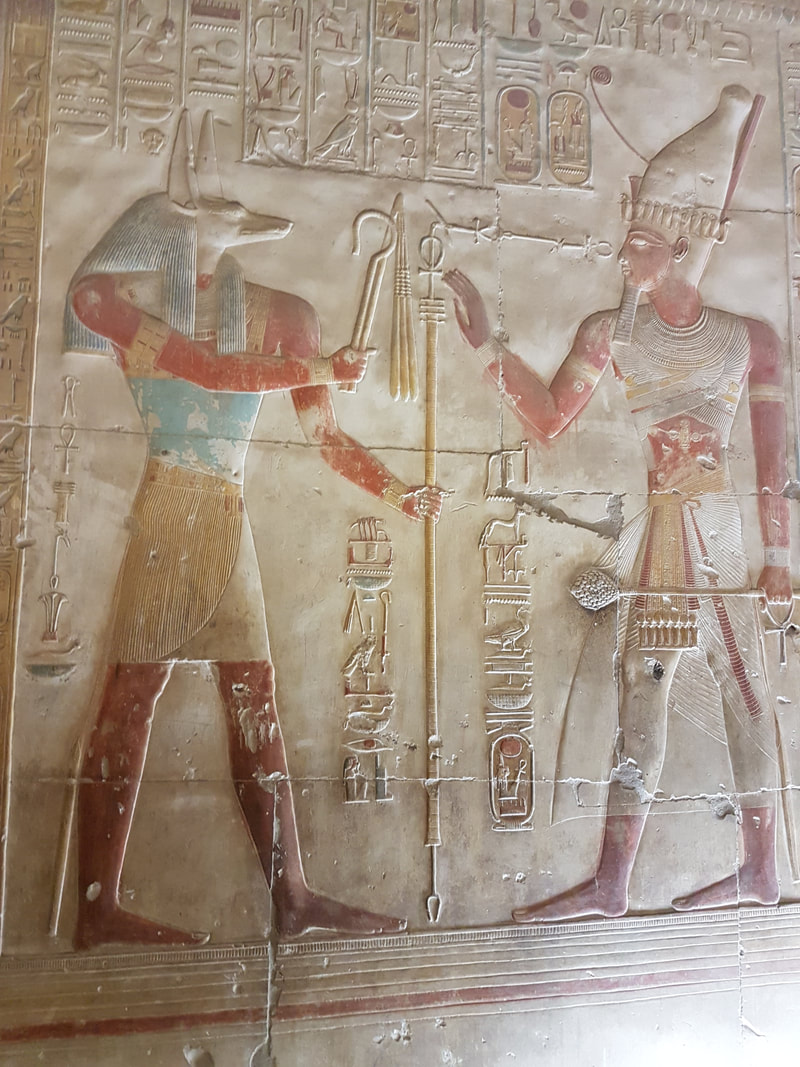

While it’s true that some PDF files will go into CAT tools (computer assisted translation tools), they don’t always go in without protest. Letters or whole sentences can turn into symbols or squiggles, making it look as though part of the text has been encrypted. This can occur both when the file is uploaded into the software or when it is exported into Word as a target document. Often, the PDF is non-editable, or there are sections that are non-editable, which usually have to be treated separately. Faxes, screenshots and scanned images will always be non-editable. There are obviously conversion apps, and I’ve mentioned some of these below, but the process is rarely completely accurate, and the original layout can be distorted or lost on the page. If the original document is not good quality this can create additional problems. Scanned pages can contain unclear, illegible or damaged text, or a fuzzy appearance on the background that translation software may mistake for characters. Logos and seals can also be problematic.

Just to be clear, CAT tools do not do the job of translation for us, but they do segment the text, making it much easier to find one’s place in a document. They make it possible to save a file in its native format, or very close to it. Of course, the translation can simply be typed out without software as it had to be done in the past, and this is probably still the safest way to retain the original page layout as much as possible and avoid losing content. But this is a time-consuming, tedious and demanding task for translators faced with tens of thousands of words on a regular basis, particularly if a file includes diagrams, graphs, charts and tables. Some items, for example stamps or other images that contain diagonal, criss-crossing or over-written text, are simply not reproducible.

There’s a wide range of readily-available PDF to Word (or PDF to another file-type) conversion apps; some are better than others. These work by optical character recognition (OCR) software, which can access the text and make it editable. Some are free, some are reasonable and some expensive, and the choice will depend on exactly what features are required. Some work on a trial basis, with the option to purchase once the trial has expired. Most claim to preserve the original format, with no loss of quality of the text, but this depends on how close the target file needs to be. Some also ask to make changes to your computer. Clearly, the details of this need to be fully understood before you take such a step. I looked into a few PDF to Word conversion apps.

The app eXpert PDF 12 both creates PDFs from Word, Excel or PowerPoint and converts PDFs into Word files. It can be downloaded free, for a trial period, and purchased for £59.99, although it seems to go up to £64.98 when you add on the VAT. Customer reviews are generally favourable, claiming that it’s quick to download and easy to install, with a good display.

Nitro Pro has a two-week trial, with the option to buy for £168 after that. This price includes customer support and product updates. The terms and conditions state that it’s also possible to purchase a subscription, but I wasn’t able to find out whether the above price was a one-off payment or whether regular payments were necessary after a set period. I couldn’t find customer reviews on the website, but PC World seem to think it’s leading the market.

Faced with a lengthy PDF document, which included extensive lists of names of medicinal products and tables with numbered headings and numbered points in columns which I had to be confident in reproducing, I recently resorted to onlineocr.net, at no cost, to convert the document into a Word file. I just needed to log in and provide a few basic details, upload my PDF, and then wait a short time to get my Word document back. I was able to try out a one-page conversion as a trial, then register to convert multiple pages. The quality was generally good. All the text was clear and legible, and the format was surprisingly well-preserved. Some characters, particularly numbers, were shown in bold when they shouldn’t have been, and vice versa, and there seemed to be a mixture of font styles and sizes in places, but it was better than I expected.

Still, the fear of losing content and/or format means that, for the most part, I avoid doing this, preferring to simply type out a non-selectable document onto a clean Word file, in the pre-technology way. So how best to handle a request to work on a difficult document? Here are my thoughts:

· Politely ask if the customer has a copy of the original Word file. This way the problem can be avoided altogether.

· If this isn’t possible, ask what the translation is needed for. If, for example, the target document is a PowerPoint to be used as a presentation for training purposes, then the format will be a crucial aspect of the service. However, if the client simply needs to understand what the text says, then you needn’t spend time making the page appear like the original.

· If you do need to convert PDF to Word, don’t settle for the first app you find. Try out a few and find the most appropriate to your document.

· In the event that you are faced with a complex document and attempts at Word conversion prove to make matters worse and you end up beginning with a clean sheet, be honest about these challenges. Making it clear to the customer how long it’s likely to take and that it will cost more than a Word document, may take the pressure off and avoid embarrassing confrontations later.

It seems that, despite the ever-advancing sophistication of technology, with better and better CAT tools, conversion apps and even programs able to convert music scores into braille, this is an area that lags behind. I have no doubt that the means of creating programs that can scan the most detailed images and turn them into text, thus surmounting this problem, will be invented very soon. Until then, I will continue to avoid non-selectable PDFs as often as I can get away with.

it.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed