I could go into the details of my recent trip Egypt: the significance of the Aswan Dam and the Ethiopian Dam further upstream; running out of water in the Nile; being stranded on a sandbank; the variety of food and flavoured tobaccos.

But this series of blogs has been entirely about communication and its importance, and how communication is achieved. As a linguist, what I found most intriguing was not the language of hieroglyphics, which I wouldn’t even attempt to comprehend, but how drawings and paintings were used so effectively to tell a story or record events and observations.

I’m no expert in ancient Egyptian art or history, but I had excellent guides who helped me make sense of the hundreds of images I took on my camera phone.

Egyptian history has a complexity that would challenge even the most arduous scholar. Broadly speaking, there are five time periods belonging to the ancient world: the Old Kingdom (2600-2160BC); the Middle Kingdom (2040-1700BC); the New Kingdom (1570-1070BC); the Late Period (600-332BC); and the Greco-Roman period (332BC-AD395). But there are also those stretches of time in between, the ones not characterised by influential rulers, such as the first, second and third intermediate periods, bridging the gaps following the Old, Middle and New Kingdoms respectively.

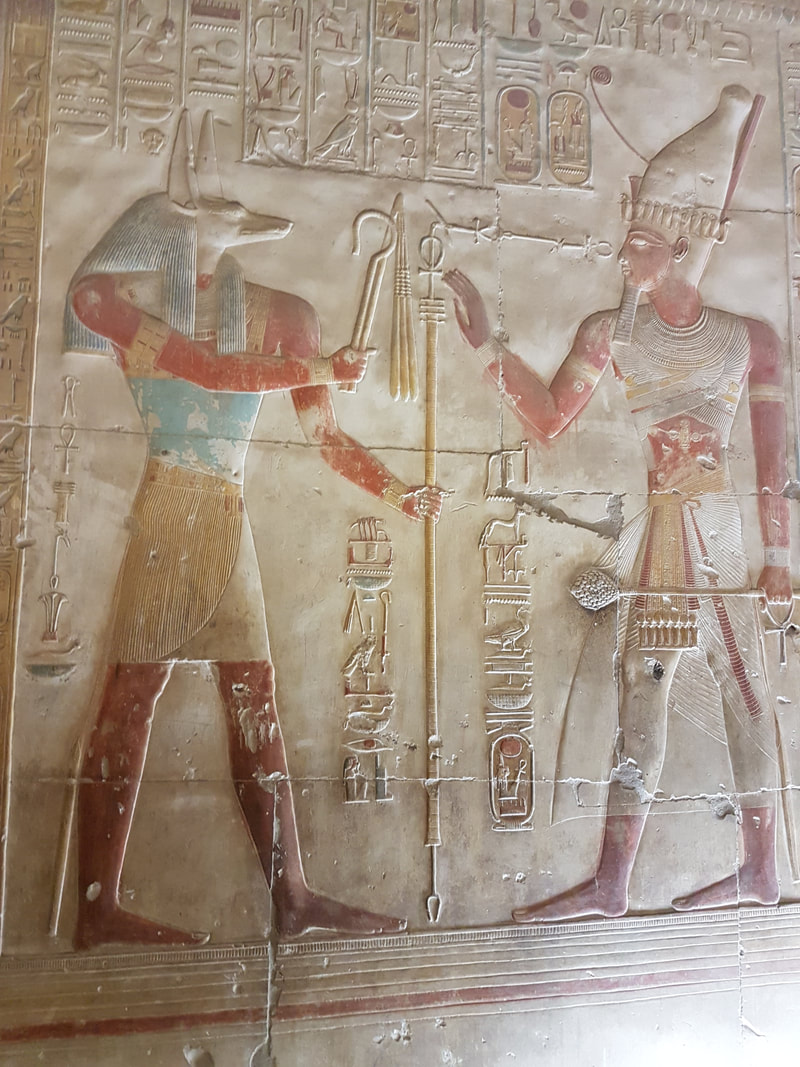

My tour began with the tombs of Rameses IV, Rameses III and Merenptah in the Valley of the Kings, followed by a visit to the Temple of Hatshepsut not far away. We then moved onto the Temple of Isis on the island of Philae. I spent a couple of days gazing, bewildered, at the images surrounding me, with no knowledge of history or the context in which to place them. It occurred to me that the best place to start was to learn the names, symbolic representations and functions of the gods in the painted figures, reliefs and statues, and how to recognise them.

Armed with guidebooks, maps, and the notes I had jotted down on listening to the guide at the various sites (yes – I’m the person at the back with a notepad and pen, straining to hear every word and hanging back to finish looking and scribbling, sprinting to catch up), I returned to the cabin and set out to memorise the information.

And so I managed to construct a simple but hopefully helpful summary. The information is difficult to condense from any one source. For one thing, worship of some gods dates back to the Old Kingdom and, over time, their role, importance, mythology, representation, and even their paternity or maternity can change. For example, Anubis was believed by some to be the son of Nephthys, while others supposed him to be the son of Bastet or Isis.

NAME

HOW DEPICTED IN PAINTINGS AND CARVINGS

MOST WIDELY KNOWN ROLE/ SIGNIFICANCE

Osiris

As a mummy, with the ceremonial curved beard, with a white crown, and carrying the flail and crozier

King of the underworld, the great god of the dead, god of agriculture

Isis

Wearing a headdress representing a throne, or wearing a vulture headdress with a serpent on the brow, or as a winged goddess or kite

A patron goddess of childbirth and motherhood, wife of Osiris, whom she raised from the dead after he was slaughtered by Set, and mother of Horus

Hathor

Most often in the form of a cow, or a woman with a cow’s ears or horns

Sky goddess. Goddess of women, fertility, children and childbirth; also of beauty and cosmetics and perfumes; and music, dance, romance, joy and many more

Horus

Usually as a falcon or man with a falcon head

Husband of Hathor and son of Osiris and Isis. Embodiment of order. Always placed in opposition to or in conflict with Set

Sobek

As a crocodile or man with a crocodile head

Associated with power and success in war, but also a protector against dangers in the River Nile

Set

Shown as a black boar, pig, donkey or another animal associated with danger or the unclean

Symbol of evil and embodiment of chaos. Believed to swallow the moon each month. Famous for battle with Horus and for murdering Osiris. Represents the desert

Anubis

Usually as a man with the head of a jackal with black fur – black being a colour associated with fertility

Guardian and protector of the dead, associated with embalming and funeral rites; he also presided over the weighing of the heart. Patron saint of lost souls. Originally god of the underworld

Bastet or Bast

As a cat or woman with the head of a cat or lion

Goddess of warfare, but later seen as having a protective role, defender of the pharaoh or goddess of the moon, or of perfumes. Protector against disease and evil spirits

Ptah

As a mummified man holding a staff

Patron of sculptors, painters, architects and carpenters, a god of rebirth and protector of Egypt

Thoth

As a man with the head of an ibis, often holding a stylus and writer’s palette

Patron of scribes and writing. Also associated with medicine, wisdom, time and magic

Nephthys

Usually as a woman crowned with the hieroglyphics that symbolise her name, which consist of the sign for a sacred temple, though can be as a kite or hawk

Wife of Set. Represents the air. Goddess of death and mourning. Believed to be the source of rain and the Nile

By the time I arrived at Kom Ombo and the Temple of Sobek, I had at least memorised a modest amount of information and felt better equipped to make some attempt to follow the stories. So what of the stories chiselled into the walls?

It isn’t always a story – sometimes more of a description of circumstances, or ongoing, eternal events. To me, some of the most beautiful paintings, dominated by the colour turquoise, appear on the ceilings of the Temple of Hathor at Dendera. By craning the neck 90 degrees and following the illustrations from one end of the building to the other, we can, for example, see how the goddess Nut gives birth to the sun every morning, then swallows it at nightfall.

Much of the artwork appears to depict the importance of staying on the right side of the gods. Pharaohs Rameses II, a fascinating, powerful but evidently narcissistic character, and his father Seti I, are seen in panel after panel making offerings to the gods. In other panels, a pharaoh is seen with Anubis, jackal-god, who places a hand upon the shoulder of the pharaoh as a gesture of safe escort. These pictures show that the death process had considerable meaning to the ancient Egyptians. Rulers wanted to be assured of a safe passage into the underworld and a welcome reception once they got there.

There are countless panels containing depictions of offerings to gods – and it is worth looking closely at the objects being offered, which are often related to the characteristics of the gods in question. For example, mortals are depicted offering mirrors to the goddess Hathor, who is associated with the cosmetic arts.

Not all images are entirely religious. Secular illustrations of Rameses II and Rameses III riding a military chariot, defeating the enemy and training their offspring to fight, can be seen in large, bold carvings and paintings on the walls at Karnak, Abu Simbal and many other places, a message of prowess and invincibility that must be perpetually understood by all.

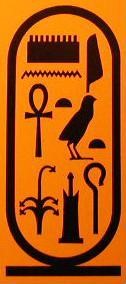

Occasionally, the identity of a ruler is not immediately apparent, and it becomes necessary to look more closely at the cartouche – an oval-shaped inscription in which the name of a king or queen is written in the form of symbols. These are always found in tombs and temples, usually above the head of the individual they belong to and are very useful in identification and dating. The idea was to eternally encircle the name of the pharaoh, so that he would be preserved after death, and to protect him against evil spirits. Below are some examples of lettering.

The symbols inside a cartouche don’t always stand for single letters, but rather sounds or syllables. If we look closely at the famous cartouche of Tutankhamun, for example, the symbol in the top left, which looks a little like a comb, represents the sound “men”, originating from a Turkish word meaning “myself”. Put together with the symbol to its right and the one below, the sound “amun” is created. On the third line, the bird symbol represents the letter “U”, with the familiar ankh symbol, the cross with a handle, which represents eternal life, wisdom and fertility, on the left. (See below)

Egyptian art was a highly skilled and jealous profession. Sculptors and painters studied in dedicated colleges for years before earning the right to work on the temples and tombs of the pharaohs. These people were highly regarded and handsomely rewarded (in the absence of currency, payment was made in the form of goods, property and food). The remains of a village were found in the Valley of the Workers on the West Bank, the bank associated with death and burial, near Luxor, which proves that painters were accommodated in comfortable, spacious houses.

As a former science teacher, I’m always fascinated by the origins of colour, and I was captivated by the striking effect of the pigments used to record history in the tomb and temple paintings. The ancients did not have at their disposal the vast array of colours enjoyed by today’s artists, yet the variety and detail with which they painted, and the visually attractive pairing and contrasting of colours, are often breath-taking. Pigments were manufactured from locally available minerals. The pigment green, for example, could be produced from malachite (Copper carbonate). Charcoal would have provided the black colour, gypsum the whites, while yellows could be produced from ochre, a source of Iron oxides. Blues could be made from azurite and reds from arsenic compounds.

Colours also had meaning. The colour black, for example, was often associated with the silt of the Nile, which was linked with fertility. There were rigorously controlled methods for mixing the paints, treating the stone by smoothing, filling and plastering before it was painted, and the laying out of scenes in a marked-off area gridded with squares, before illustrating could even begin. Grids would have helped the artists to proportion the figures correctly. The work was subject to scrutiny and correction by master artists, and the final painting was carried out one colour at a time.

It is widely accepted that Egypt owes much of the rare degree of preservation of its historical artefacts and monuments, and thereby its thriving tourist industry, to its arid climate. Annual rainfall is extremely low. When looking at this work, it is certainly difficult to believe that these images have survived for thousands of years. But this probably means that we fail to acknowledge the extent to which artists went to ensure survival of their work. Rather than painting into a thin layer of wet plaster, as done in conventional fresco painting, analysis reveals that paint was applied to dried plaster. Varnish or resin was also applied after painting. The artists’ attention to detail is phenomenal.

The Ancient Egyptians were not the only ancient civilisation to write in pictures and symbols. Pictorial Jiahu symbols dating back to the 7th millennium BC have been found on a range of Neolithic sites in China. During the 4th millennium BC the Sumerians were also using impressions in clay to keep accounts. There are many examples of early forms of written communication at times when exchange of messages between groups of people was slow and dependent on the most basic of tools and materials, and equally basic forms of transport.

The lengths the Egyptians went to in order to communicate and to leave us their messages made me consider the throwaway nature of our exchanges today, and how reliant we have become on instant messages and equally instant responses.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed