It’s been a few years since I last set foot in a classroom, but I spend a few hours a week giving home tuition to secondary school pupils too ill to attend school. As anyone who has tutored individuals will know, working on a one-to-one basis can provide surprising insight, not only into areas of difficulty, but also into various misconceptions and stumbling blocks that students may be experiencing. One source of confusion is the periodic table.

Unless you’re competing in serious science quizzes – your average village pub quiz probably won’t have more than one question on the symbol for a chemical element – learning the periodic table off by heart is probably something most of us can live without. Even A level students have one provided in their exams, or at least whatever crucial information they need from it. But for most school pupils, it’s worth remembering enough to iron out some sources of confusion. One of these is the apparent mismatch between the names of the elements and their symbols.

For example, when discussing active transport in Biology, and the Sodium-Potassium pump used to move ions across animal cell membranes, youngsters are often confused by the symbols Na⁺ and K⁺. Asked to write a chemical formula for a compound containing sodium, they will usually, unless they have spent time committing the symbols and charges to memory in preparation for a test, begin by writing a letter “S”. To my mind, this raises an interesting question. Why do we assume that the symbols or names are taken from the English language? Is this the arrogance of the English-speaking world? The symbol S is for Sulphur, while that of Sodium, Na, is from the Latin word Natrium, while K is for Kalium, an Arabic word meaning Potassium.

The periodic table is a fascinating collection of words and symbols originating from many languages. We have Nickel, symbol Ni, derived from a Swedish word, Kopparnickel, which was used to describe the ore from which it was extracted. The symbol for Lead, Pb, comes from the Latin Plumbum, which is the source of the word plumber, since Lead was formerly used for water pipes before we became aware of its toxic nature. The Greek word Kryptos has provided the name Krypton. The word was used to mean “hidden”, because of its invisibility and undetectability, having no colour, smell or taste.

Sometimes the origins of the name have quite a detailed and interesting history. You will forgive me for quoting from the chemical element name etymologies offered by Wikipedia. For example, the name Cobalt comes from the German Kobold, meaning “evil spirit”. The historical explanation for this is that miners believed that it contaminated other, more desirable metals. Its compounds are also poisonous. Some chemical elements are named after gods. Uranium, whose ores are a well-known fuel source in nuclear power plants, is named after the planet Uranus, which itself was named after a god of sky and heaven in Greek mythology. Vanadium comes from the name Vanadis, another name for Freyja in Norse mythology. Others are named after countries or geographical areas. Marie Curie named one of the elements she discovered after her Polish homeland, hence Polonium. Others are named after the individuals who discovered them, or made a scientific discovery or invention that warranted the distinction of having a chemical element named after them. The one that springs to my mind is Mendelevium, since it is Dmitri Mendeleev we have to thank for conceiving the periodic table in the first place. The brilliance of this scientist cannot be overstated, but that is for a different account.

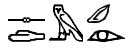

The chemical symbols too have some interesting back stories. One theory about the symbol for Antimony, which is Sb, short for the Latin name, Stibium, is that it is borrowed from an ancient Egyptian word, sdm, or

There are countless other examples of intriguing stories behind the names and symbols of the chemical elements. As well as a rich source of fascinating facts and anecdotes, the periodic table is an excellent example of international collaboration and the contribution of many languages. A chemical formula for a drug or a chemical equation for the preparation of a product is a shorthand way of providing a large amount of information in one line, which can be understood by speakers and readers of a vast number of languages. How wonderful to have an effective and rapid means of communication across borders, and what better way to motivate language or science students than to share so rich a history as that of the discovery of the elements, their uses and their eventual organisation into a logical structure that can be understood by all.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed