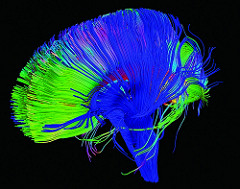

Photograph: NICHD/P. Basser/Flickr

Photograph: NICHD/P. Basser/Flickr It's an incredibly complex and distressing disease, and I've felt compelled to find out more about it. One of the things I've been fascinated to discover is that learning a second language can delay the onset of dementia.

Much research remains to be done on both dementia – a brain disorder that affects communication and performance of daily activities – and Alzeimer's disease – a form of dementia that specifically affects parts of the brain that control thought, memory and language. Research is challenging: it's difficult to monitor people over decades; brain dissections can only be performed once people have passed away; and brain scans are not normally done until a patient has started to show signs of dementia, so it's rare to be able to compare them with the patient's younger, healthier brain.

But notable studies have been done. One, published by the Alzheimer's Society in 2013, found that learning a foreign language can delay dementia by four and a half years on average. The Indian Department of Science and Technology looked at the records of 648 people with dementia - 391 of those were bilingual, and they showed symptoms of dementia much later than those who only spoke one language. This was even the case for people who could not read and write – illiterate bilinguals also developed dementia years later that people who only spoke one language.

An interesting, retrospective study was carried about between 2008 and 2010. In Edinburgh, 853 people who had undergone an intelligence test at the age of 11 were retested in their 70s. The test included speed of processing, memory, letter and number sequencing, pronunciation and verbal reasoning. No immigrants were tested – or anyone who was likely to have been bilingual from childhood. Almost a third of them had learned a second language, and these people performed better in the intelligence test than those who only spoke English. Bilinguals outperformed on predictions made based on their intelligence in childhood. The study, researchers concluded, suggests that learning a foreign language protects the brain against age-related cognitive decline – even when someone learns a second language as an adult.

The HelpGuide, a website that gives advice on mental, emotional and social health, suggests that for older adults, just 10 mental training sessions can improve cognitive function dramatically, with lasting benefits. The exercises it mentions include problem-solving tasks, memorising lists and spotting patterns – precisely what it takes to learn a language. It seems to me that if you're going to do these kinds of exercises, you might as well be learning something useful that will enhance the quality of your life, especially if you're still able to travel.

The physical act of learning a new language, of consciously committing new vocabulary to memory, spotting patterns in grammar and applying rules, overcoming the shyness of speaking to someone in their native language – all this requires considerable effort. You can almost feel the brain working hard. It is this pain barrier, the trudging effort required, that causes so many people to give up after a few lessons in a foreign language. When my mother, now struggling to complete a sentence on the same topic in her native English, began attending evening classes for conversational French, she didn’t persist for long. I now wish I’d encouraged her more.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed